Human rights are the rights we are all entitled to simply by virtue of being human. They are based on values such as fairness, respect, equality and dignity but they are more than just nice ideas; they are protected in law. The European Convention on Human Rights and the UK’s Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) set out rules for how governments must treat individuals. You can read the Human Rights Act in full on the legislation.gov website.

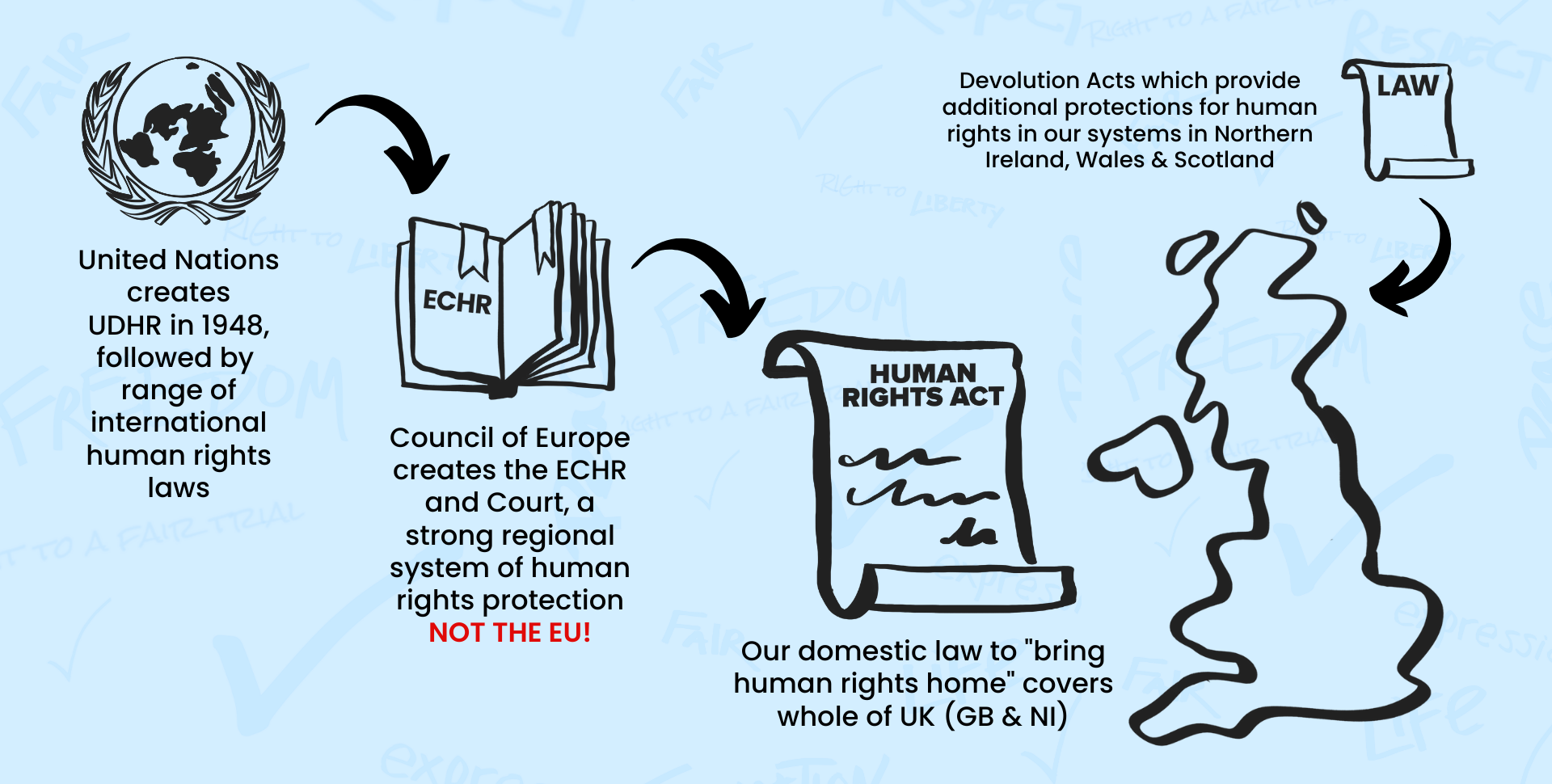

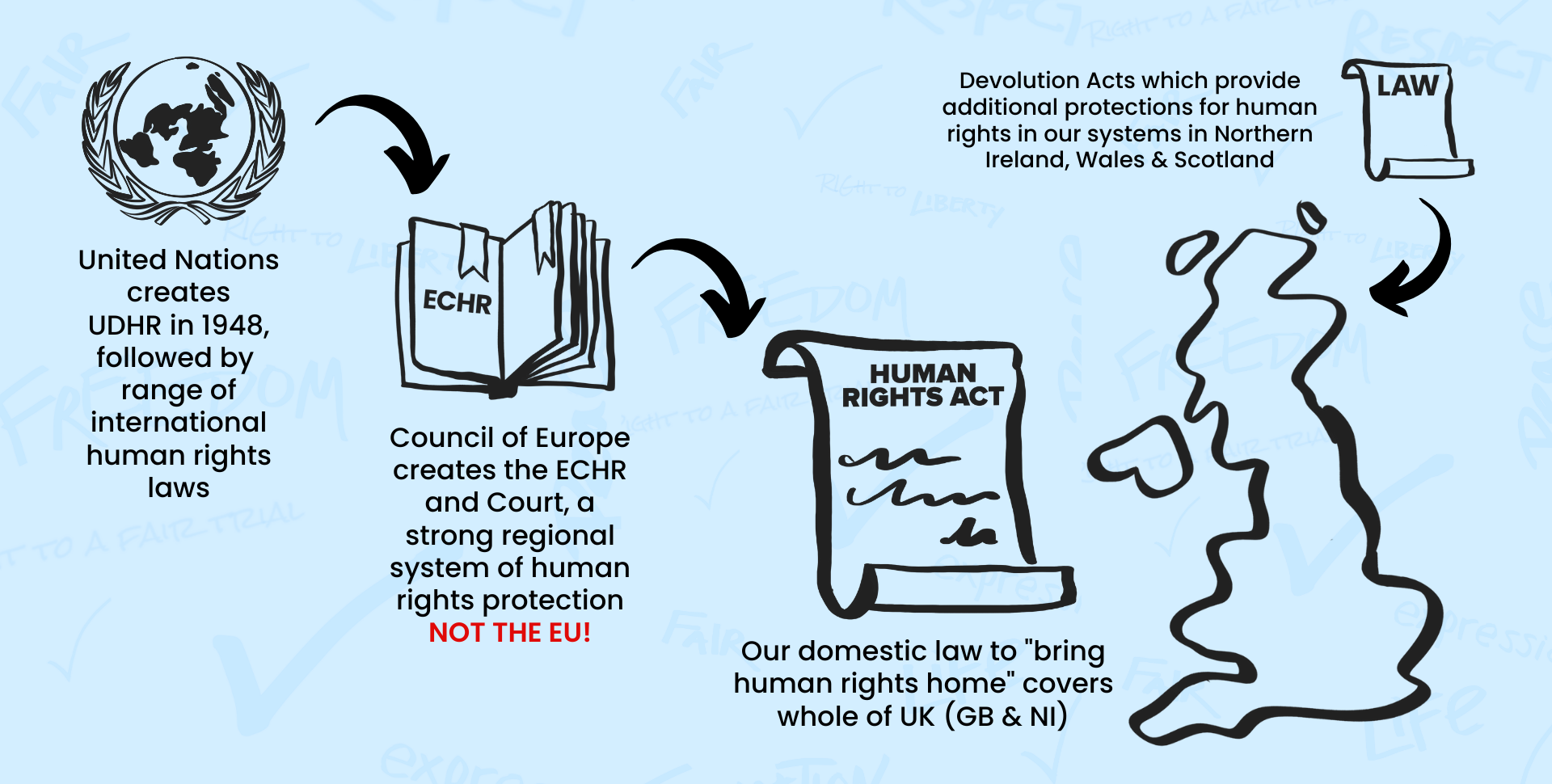

After the horrors of World War II, it was recognised that, while democracy is a partial check on power, it is not enough. We need to ensure that elected governments are not left to decide who matters and who doesn’t. World leaders committed to protecting the rights of all citizens by signing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. While not legally binding, this laid the foundations for the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and our HRA. Our HRA was passed by Parliament and supported by members of both the Labour and Conservative parties.

Our Human Rights Act takes 16 of the fundamental human rights written into the European Convention on Human Rights and puts them into UK law. This means they can be enforced in UK courts rather than having to go the European Court on Human Rights in Strasbourg.

The UK Government and people who work for public bodies, such as doctors, social workers, teachers and judges, have a responsibility to respect, protect and fulfil all our human rights. If they do not, the people affected can bring a legal case against them.

Some of our human rights are absolute, meaning they can never be interfered with. Others are non-absolute, meaning they may be restricted in certain circumstances, but only if the Government can show that the restriction is:

The rights in our Human Rights Act are also covered by the devolution arrangements in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Under the Scotland Act 1998, the Government of Wales Act 2006 and the Northern Ireland Act 1998 each country has its own legislature (law-making bodies like parliaments) and government. These Acts also say that if the legislatures cannot make laws that are not compatible with the rights in the ECHR. If a court finds if the legislatures have made a law that is not compatible with those rights, it will say the law isn’t valid.

This is different to laws made by the UK Parliament. Courts can’t change or disapply a law made by UK Parliament. If possible, courts will try to interpret the law in a way that is compatible with human rights but if this is not possible, they can only declare that it is incompatible with human rights and it is then up to UK Parliament to decide whether or not to change the law.

Human rights are sometimes thought about as covering two areas: civil and political rights (protecting our freedoms), and economic, social and cultural rights (protecting our rights to live with dignity, safety and health).

Traditionally our 16 HRA rights have been called civil and political. However, it is really important to remember that our HRA is a “living instrument”. This means the way it is interpreted and the protections it offers needs to adapt and develop in line with our society’s progress e.g. the right to private life has helped people challenge the use of CCTV cameras, even though these weren't around in 1950 when the rights were first written.

A significant proportion of BIHR's work focuses on areas traditionally seen as economic and social, such as health, housing, care provision and social support. As the European Court of Human Rights has itself noted, “there is no watertight division separating" economic, social and cultural rights away from the rights in the HRA (and Convention). We believe the potential of the Human Rights Act, to enable people to flourish across all aspects of their lives, has not yet been realised. We are committed to enabling people to make the best use of their protections and the duties of public officials under the Human Rights Act, using this legal framework to create social change beyond the courtrooms.

The Human Rights Act protects everybody in the UK, and the rights contained in the Act belong to everyone in the UK. This is a key feature of human rights- they are universal and apply to everyone. They are not gifts from the Government or rewards that you earn. You do not need to be a UK citizen to have these rights under the Human Rights Act. The rights in the Human Rights Act are there for everyone; they act as a safety net and offer protection for those who may be the most vulnerable.

The starting point for human rights is the same for everyone, no matter who they are. For some people however, this may require more action from the state or public authorities to realise the rights in the Human Rights Act. The Human Rights Act encourages an individualised approach which means that realising human rights may mean different things to different people.

Section 6 of our Human Rights Act 1998 puts a legal duty on all “public authorities”, and their employees. There are two different types of “public authority” that must respect our human rights:

The duties under the Human Rights Act can be shared. This means that a variety of public authorities may have overlapping duties for an individual.

The Human Rights Act places a duty on public authorities to respect, protect and fulfil our human rights across their actions, decisions, policies and services.

The duty to respect people’s human rights means that public authorities must not restrict them or try to breach them. This is known as a negative duty. It means that staff should avoid interfering with someone’s rights unless it is absolutely necessary to protect that person or others from harm.

The duty to protect people’s human rights means that by law, public authorities must step in and take positive action to protect people from harm. This is known as a positive obligation. It could involve protecting a person from harm by another, non-official person, for example a family member or carer. This duty is usually called safeguarding. It could occur in domestic abuse cases, where the police are aware of what is happening but fail to step in and prevent any further harm from occurring.

The duty to fulfil people’s human rights means investigating when things have gone wrong and putting measures in place to stop it from happening again. This is also known as a procedural duty. It means that public authorities should take steps to strengthen access to and the realisation of human rights. This was the duty used by the Hillsborough families to get justice through an inquest.

These duties apply to all the rights in the Human Rights Act. The public authorities that we work with tell us that they do not see these duties as a burden, but rather as an important tool to help them make rights-respecting decisions.

The Human Rights Act applies across the UK. The rights within the Human Rights Act, brought into UK law from ECHR are interwoven into the devolution arrangements in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Scotland Act 1998, the Wales Act 1998 and the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (which is part of an international peace process) established devolved legislatures and administrations. Each devolved nation has a range of issues for which it is responsible, many of which impact on human rights.

All the devolution arrangements prevent the parliaments/assemblies in devolved nations from passing laws which may be incompatible with Convention rights, as set out in the Human Rights Act. If a court in the devolved nations finds a law to be incompatible with human rights, it can be disapplied, because such a law would be outside the powers delegated to those bodies (“ultra vires”). This is not the same for UK Parliament which is sovereign. The mechanisms in the Human Rights Act and its position in devolution arrangements are part of what makes it such an innovative, distinct piece of legislation. In devolved nations, like Scotland, the HRA is a crucial building block for increased rights protections.